Know the Law About Contracts

Between Parents and Child Care Providers

This publication is intended to provide general information about the topic covered.

It is made available with the understanding that the Child Care Law Center is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice. We believe it is current as of December 2021, but the law changes often. If you need legal advice, you should consult an attorney who can specifically advise or represent you.

Printable Version:

Child care involves a business relationship between a parent and a provider. Each person expects certain things from the other, whether or not these expectations are written down in a contract. This publication is designed to introduce parents and providers to contract law, and what benefits contracts can bring to their interactions. This Know the Law focuses on contract law in the state of California.1

1 Special rules apply to families receiving subsidies, and to child care providers who are paid with subsidies. This publication is not designed for use when child care subsidies are involved.

1. What is a Contract, and What Makes a Contract Legally Binding?

California law defines a contract as “an agreement to do or not to do a certain thing.” California law does not require that a child care contract be in writing.

Contracts do not have to be long or written in legal language to be legally binding. To create a contract for child care services, all that is required by the law is (1) mutual consent to an agreement and (2) an exchange between the child care provider and the parent.

A mutual agreement shows a “meeting of the minds”; both the parent and the provider must understand the rules that are being agreed to. The exchange means that both sides give up something and receive something under the contract. In other words, the parent agrees to abide by the provider’s rules and pay in exchange for child care, and the provider agrees to care for the children in exchange for receiving payment.

2. What Type of Exchange is Needed to Make a Contract?

The exchange must be bargained for, and each side must either do something or promise to do something in return for the other side’s action or promise.[1] But the exchange gets tricky when one side agrees to do something as a favor or gift. For example, if one day at pick-up time a parent spontaneously offers to repair a broken climbing structure, then backs out later, she has not broken any contract. The reason is that the promise to do the repairs was merely a gift to the provider. The parent was not promising to do it for compensation, so there was no

exchange, and there is no enforceable contract.

[1] Id.

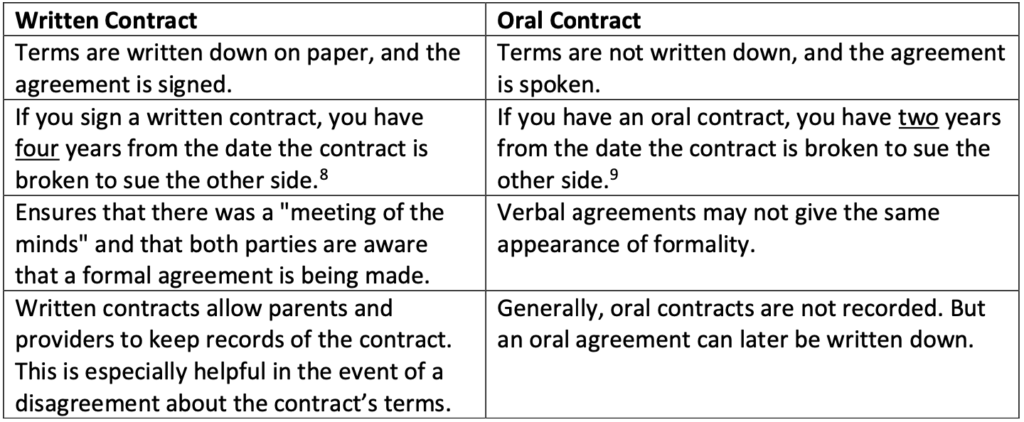

3. What Types of Contracts Are there and How Are They Different?

4. Are there Advantages to having a Written Contract?

A written contract sets forth responsibilities for providers and parents while the child is in the provider’s program. Of course, even without the written contract, parents and providers have certain implied responsibilities (e.g., to pay for the child care, to provide child care). The written contract can make these responsibilities very specific. If a parent believes a provider broke the contract, the parent can sue the provider, and vice versa. A written contract generally also trumps any negotiations that occurred before the contract was signed.[1]

[1] Cal. Civ. Code § 1625. (West 2012)

5. Will a Contract be Enforced if One Side Signed the Contract without Reading it?

In California, a person who signs a written document that seems to be a contract will be treated as if they have agreed to all its terms. Individuals cannot escape liability by claiming not to have read the contract or by not actually reading it.[1] Parents who cannot read well should have contracts read to or explained to them. Parents who do not speak English fluently should ask that contracts be translated into their preferred language. If the native language of the families a provider serves is: Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog, Vietnamese, or Korean, and the provider negotiates the contract in that language, the law explicitly requires that the contracts be translated into that language, whether or not parents ask.[2]

If the person who writes the contract (most likely the child care provider) creates a contract that has ambiguous or uncertain provisions, it will be difficult to enforce it against the other side. In such cases, contracts are interpreted against the party who caused the uncertainty to exist.[3]

[1]Norcia v. Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC, 845 F.3d 1279 (9th Cir. 2017), cert. denied, 128 S.Ct. 203 (2017).

[2] Cal. Civ. Code § 1632. (West 2012).

[3] Id. § 1654.

6. Can a Parent or Provider’s Behavior Create or Change a Contract?

Although it is not very common, California law sometimes recognizes implied contracts. To determine whether an implied contract was created, California law states that the parties’ conduct determines if there is an implied contract, and, if so, what the terms are.[1] This means that a parent or provider’s conduct over a period of time may show a mutual agreement to change a contract. It is important to note that even if neither side verbally or in writing agrees to change the contract, a parent or provider may appear to change what is written in the contract by her actions.

If there is an implied contract, it is possible the written terms might not be enforced by the court. For example, a child care contract might require a fee for late pickup. However, if the provider never enforces that provision (e.g., there are multiple times when a parent was late for pick up but the provider never charged the parent a late fee), then the court might determine that contract provision is unenforceable. By allowing late pickups without a fee, the provider’s conduct implied a change to the contract.

[1] Id. § 1621.

7. Can Providers use Contracts if the Child Care Home is Exempt from Licensing Requirements?

Yes. California is one of a number of states that exempt certain types of child care facilities from licensing. These exempt facilities include those caring for the children of only one family in addition to the operator’s own children and any arrangement for the receiving and care of children by a relative.[1] Exempt providers can use contracts and enforce the contracts in court if necessary.

[1] Cal. Health. & Saf. Code § 1596.792(d), (f).

8. How Does a Provider Create a Contract?

A contract can be drawn up on an individual basis with each parent at enrollment time, or providers can develop a standard “Child Care Contract” to use with every parent. Many providers use a standard contract with some blank spaces for writing in any additional agreements reached with the family based on its particular needs.

9. What Types of Provisions Can a Provider Write into the Contract?

Here are some common examples of provisions in child care contracts:

- Enrollment and Withdrawal from the Program: Required immunizations for enrollment, notice requirements for withdrawal;

- Hours and Fees: When payment is due and in what form, hours of operation, penalties for late pick-ups;

- Vacation and Days Off: Days the program is closed, which holidays are paid holidays, notice requirements for parent vacations;

- Food: Whether meals are provided, requirements for special diets;

- Clothing and Supplies: Whether diapers are provided, requirement to leave an extra change of clothing with the child;

- Illness and Medication: Notification of parent if child is ill, requirement to have parent authorize all medication given to the child, policy not to care for ill children or rules for exclusion of ill children;

- Miscellaneous: Discipline policy, nap policy, toilet training policy.

10. If the Contract Has a Set of Rules Attached, Are Parents Also Obligated to Follow Those Rules?

Yes. Rules that are attached and referred to (known as “incorporated by reference”) in the contract are as legally binding as the contract itself. In California, even documents that are not attached are considered part of the contract if the parties intended them to be part of the agreement.[1] Providers often include a set of rules to let parents know how the child care program is run. They usually include such things as schedules, discipline policies, and other requirements (e.g., requiring parents to provide a change of clothing). It is important to read the contract and the attached rules before you sign the contract, and parents should sign only if they want to follow the terms of the contract and the attached rules.

[1] Cal. Civ. Code § 1625.

11. Do State Laws Affect Child Care Contracts?

Yes. State (and federal) laws always trump contract provisions.[1] If a contract says something different from the law, the contract provision is unlawful. Because many child care providers are licensed, licensing laws are particularly important. For example, licensing law states that providers may not use physical punishment, like spanking. So even if a provider wrote in her contract she spanked children and the parent agreed and signed, that contract provision would be unlawful and invalid. Licensing laws require providers to follow certain rules even if the contract says something different.

[1] Id. § 1667.

12. What Should Parents Do Before Signing a Contract with a Child Care Program?

Child care resource and referral agencies usually have pamphlets and helpful advice about how to choose a provider wisely. Community Care Licensing, the agency that oversees licensed child care providers, will have information about the provider, including information about past violations of licensing laws. Parents can ask questions about the contract, and may choose to look for another provider if questions are unanswered, or if the parent and provider cannot reach an agreement on certain issues.

13. Can Parents Ask to Have the Contract or the Rules Changed Before Signing it?

Yes. Any contract and attached set of rules can be modified if both the provider and the parent agree on the changes. Any changes should be written them down with the date recorded, and included them as part of the contract.

14. Can the Contract or the Rules be Changed after the Parent and Provider Sign It?

Yes. Parents and providers can mutually agree at any time to change the contract. Generally, if a parent and provider sign a written contract, any changes to it should also be in writing. However, California law does allow verbal modifications of written contract provisions if the new oral agreement is either bargained for or is actually executed.[1]

For example, a parent and provider might decide to change their contract so that the parent can pick up her child later and is charged a higher fee for it. This is a new bargain—both the parent and the provider are promising something new and receiving something new in return.

Or, the parent and provider might decide to change the contract so that the pickup time is later, but the price remains the same. This would not be a new bargain, but once the provider allows the parent to pick up her child later and still pay the same price, the deal is considered “executed.”

Still, writing down any changes is the best practice because it ensures greater clarity and protection for both sides to a contract. A rule of thumb is to reread contracts once a year and, if things in the program have changed or the parents suggest changes, revise the contract and rules. Such changes should be written, dated, and given to parents for signature.

[1] Id. § 1698.

15. Can Providers use Contracts to Protect Themselves against Negligence or Other Claims?

Probably not. Providers sometimes try to include waivers, releases, or other “exculpatory clauses” in their contracts to protect themselves against liability for any harm suffered by the children in their care. California law bans contract provisions that exempt anyone from responsibility for her own negligent violation of the law.[1] Child care is important to the public interest, therefore courts in California have found such contract provisions to be invalid because they violate public policy.[2]

[1] Id. § 1668.

[2] For a good example of ineffective use of waivers, see Gavin W. v YMCA of Metro. Los Angeles, 106 Cal.App.4th 662, 131 Cal.Rptr.2d 168, 3 Cal. Daily Op. Serv. 1693, 2003 Daily Journal D.A.R. 2157 (2003) (holding that contracts for child care services are “affected with a public interest” because child care is indispensable and because demand greatly exceeds supply in California, and that contract provisions exculpating a child care provider from its own negligence are void because they violate public policy.)

16. What Happens if the Parent or Provider Breaks the Contract?

If a parent or provider breaks an important rule of the program—referred to in legal language as a “breach”—the contract may give the other person a reason for suing or threatening to sue. In other words, the contract could be the basis for a lawsuit in small claims court.[1]

If the provider fails to comply with the contract in a significant way, the parent is no longer legally obligated to comply with the contract either, and vice versa.[2] Practically speaking, though, if a parent wants a child to remain in the program, the parent may continue to honor their part of the contract if the provider’s violation isn’t really important to them.

If one side does violate the contract, the other side may decide to sue in small claims court for money that is owed. This usually occurs when the parent has paid in advance, or when the provider asks the child to leave care without giving enough notice. For example, if the contract requires the provider to give parents two weeks’ notice before terminating a child from the program, the provider is in breach if she removes a child from care without giving two weeks’ notice.[3] A parent who sues because of this breach may be entitled to stop paying the provider, a refund of any advance payment, and possibly also to payment of any wages lost if the parent missed work while arranging replacement child care.[4]

[1] A breach of contract claim can be brought in any civil court. This Q&A focuses on contract claims in small claims court.

[2] Cal. Civ. Code § 1688.

[3] The parent will also be in breach if she removes her child without giving the provider two weeks’ notice. Even though the contract does not explicitly require the parent to provide notice, the same obligation the provider has is implied on the parent.

[4] Cal. Civ. Code §§ 3300-1.

17. What is Small Claims Court?

Small claims court is a local court where anyone can sue another person for limited amounts of money. Although lawyers cannot represent either side in court, parties may speak to a lawyer before their hearing. The hearing is before a judge or commissioner, who is sometimes a volunteer lawyer. It is a quick process and the decision can be made at the end of the hearing or within a few days.

In California, people can use small claims court if they have a dispute with a person, company, or government agency involving a maximum of $10,000.[1] People sue for money (also known as “damages”). The amount of money the injured person can win in a suit is the amount of damages actually caused by breaking the contract, or the amount of damages that the violation is likely to cause.[2]

Small claims court tends to be informal. No one can make the kind of “objections” that lawyers make on television shows, and there are no juries. Cases move quickly, with a hearing often scheduled in a matter of weeks. Anyone (U.S. citizens and immigrants) who is at least 18 years old and mentally competent may file a claim in small claims court. The small claims advisor can answer questions and explain the process. Please see the “Useful Resources” box below for more information.

[1] Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 116.221.

[2] Cal. Civ. Code § 3300.